Hermitage on Wheels

Ostensibly, I hit the road back in September to travel west, immerse in nature, and spend quiet days on writing projects. It was not until recently that I finally realized why I needed to travel: to experience an extended contactless personal retreat.

I have long desired to spend time on personal retreats, whether to an isolated cabin in the woods, or some stone-walled monastery inhabited by faithful monks seeking silence and contemplation. There are places such as monasteries, abbeys, and other spiritual retreats, where one can experience such times for a fee. But that was before Covid times and now such an endeavor is probably not a good idea. And to be clear, my contemplative reasons are not religious in nature, as would be monks around me or the influence of a monastery.

I have spent almost a month at this long-term visitor area inside an expansive BLM property on the far southeastern border of California near Yuma, AZ. Until last week, when I decided not to attend a van meet up at Quartzite from a concern for socializing with others at a time when Covid contagion is once again a high risk, I finally realized the other unknown reason I wanted to stay where I was: this semi-isolated desert place pulled me here for the solitude and sameness of days, two important ingredients for any retreat.

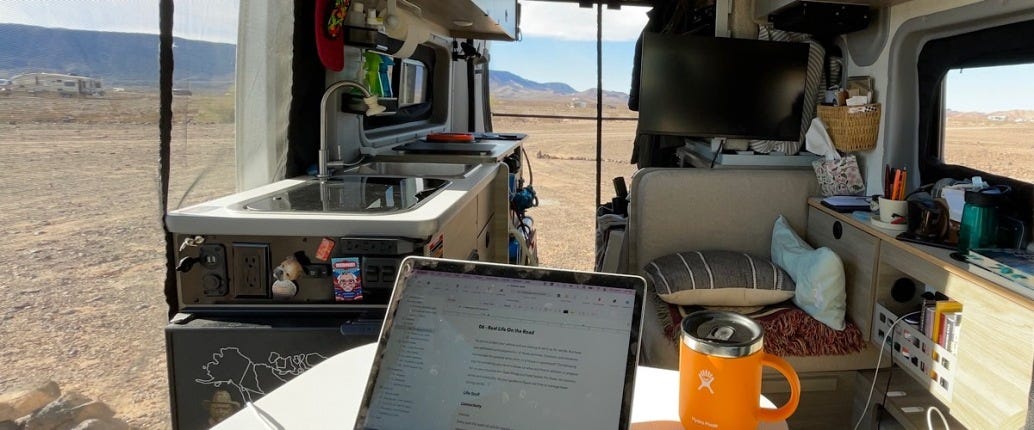

While, unlike hermits of early Europe who shunned society to live in stone huts void of any civilized trappings, and eating barely subsistence foods, I live in this steel cave with windows, this ”hermitage” through which I can enjoy and be inspired by the beauty of desert sunrises, and the calming effect of multi-colored surrounding hills and mountains throughout the sun’s arcing path across the desert winter’s sky. I make no apologies for eating well as opposed to the ancient hermits, nor for the breaks I take some nights to binge Netflix. My interpreted hermitage is about an open environment to spend time in contemplative and creative pursuits, but not in perpetual suffering in search of being worthy as did the hermits. I am, in my mind, feeding my practice of becoming a more effective solitary for my improvement.

Plans now are to live for the remaining two months here in my winter hermitage, spending time in quiet walks, deeper reading, even deeper journaling, and a renewed focus to complete several open writing projects. I am not completely without contact, since at least once a week I have to journey to Yuma to replenish supplies, and there is the weekly small talk at the RV dump and water stations here plus with volunteers at the service center where I get packages and propane when needed. But mostly, it is a solitary experience, and that is my need for now.

Even today in an expanded, though at times inconsistent, acceptance of behavior, many people still perceive someone walking alone, reading alone, spending a lot of time alone as lonely, or at least deficient without a partner or constantly in the company of many. The media and others would label such people as “singles,” as though the only measure of reference is “opposite of married.” Historically, some of our best creatives have been what is now coined as a more apt phrase—solitaries—for those who enjoy their own company more than that of others, such as Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and the artist Cezanne. The famed Trappist monk Thomas Merton first coined “solitaries” to be a word independent of gender and without the burden of societal’s increased value for those married.

What many do not understand is that living alone or enjoying time alone is not a habit nor a “what else can I do?” predicament. A habit is a way of living, followed because you did it yesterday and the day before and so on, and is a way of being that controls you and your actions. A practice is a way of living that you create and renew each day, one that you control deliberately, and that is open to possibilities unknown. That is why such things as yoga and meditation practices and not habits, because each time they take us further, not just repeat what we did last time. Being a solitary is a lifestyle innate from within, not a choice or the best of one’s options, but deliberate and in one’s truest nature, one more open to intellectual and creative growth than any habit-driven existence.

In the silence of my solitary walks I hear the voices of the trees. I hear them singing of a solitude that admits no loneliness.

– Fenton Johnson,

from the book “At the Center of All Beauty:

Solitude and the Creative Life”